This medical research is relevant to all human kind.

Cystic Fibrosis research relevant to all humankind

About Cystic Fibrosis WA

Our mission is to contribute to the social, physical and emotional wellbeing of those affected by cystic fibrosis and to assist in the promotion of research.

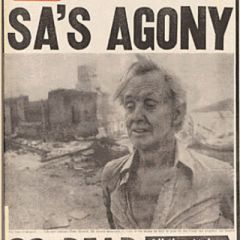

Superman actor Christopher Reeve was likely killed by a microbial monster of a different kind. Picture: Supplied

Cystic Fibrosis WA is currently funding research through the Australian Cystic Fibrosis Research Trust (ACFRT), which is investigating how Nitric Oxide may be used to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR) by breaking down biofilms.

AMR has been identified as the most pressing issue for the survival of the human race. So while this research is being funded through the ACFRT, it is immediately relevant to every human being on the planet.

But what on earth is a biofilm? And why should we care?

Well, who can forget Superman actor Christopher Reeve? When he fell from his horse in 1995, he was left quadriplegic, but undefeated. Ultimately, however, this super man was beaten by a microbial infection - and Reeve died on October 10, 2004.

It was probably not a superbug that brought down Superman. It was more likely a microbial monster of a different kind.

A biofilm bears little resemblance to the individual rods or sphere-shaped cocci traditionally studied in biology class. It’s much more like a living animal composed of multiple cell types – bacteria, archaea, fungi, yeasts – communicating and working together. They cooperate to create a near-invincible slime shield. That makes biofilms almost bullet-proof when it comes to antibiotics.

Canadian microbiologist William Costerton found that the fast-flowing waters of mountain streams were almost sterile, yet the rocks were colonised with slime-forming bacteria. Though biofilms were well known from marine environments, these ones got Costerton thinking. If bacteria could gain such a tenacious foothold in a fast-flowing mountain stream, how might they behave in the human bloodstream?

Historically, microbiologists had pictured bacteria as floaters, existing in a “planktonic form”. But thinking about the slimy films, Costerton began to ask if these types of microbial colonies could explain some of the more persistent infections of the human body.

He thought of the lungs of his son, who suffered from cystic fibrosis (CF) – they also appeared to be covered in a slimy bacterial layer.

In 1977, Costerton attended a meeting on lung infections in CF in Montreal. There, he met Danish physician and CF specialist Niels Høiby, who had also been studying the clumps of slimy bacteria from the sputum of his CF patients. “I’d never seen anything like it,” he recalls. “The clumps resembled frogs’ eggs.” He proposed the slime might be the reason immune cells could not clear the infections.

Høiby and Costerton formed an alliance to raise medical awareness of this microbial phenomenon. Costerton was a great communicator and played the lead role. When Costerton died in 2012, he was known as the father of biofilms.

Cynthia Whitchurch - based at the ithree institute at the University of Technology, Sydney - is pursuing the interest that captivated her since doing her PhD. How do bacteria move en masse across a surface?

How do the individuals coordinate their behaviours? One insight came in the 1990s with the discovery of how Vibrio fishceri, a luminescent bacteria that lights up the underside of the Hawaiian bobtail squid, coordinates its behaviour.

Balmy Hawaiian nights are often brightly lit by moon or star light, so the squid needs counter-illumination if it is to stealthily hunt the creatures swimming below. But the low densities of Vibrio found in the ocean do not glow. Much as a committee will not vote until it reaches a quorum, Vibrio first needs to reach a density of 10 billion cells per millilitre of water before it casts a light. Their breeding ground is a cavity on the underside of the squid called the light organ. (It also has shades in case the night is cloudy.) Each evening the bacteria reach the necessary quorum and begin to luminesce. Each morning the squid turns downs the wattage by venting the Vibrio, perhaps to save nutrients.

It’s an extraordinary story, but what intrigued the microbiologists was how did free-living bacteria, supposedly oblivious to each other, sense each other’s presence?

“To me, the most fascinating understanding is that they can talk in order to c-ordinate their functions,” says Whitchurch. That mechanism, dubbed “quorum sensing”, is also key to the formation of biofilms.

Quorum sensing is the key to the formation of biofilms

When microbes hit a tooth or an artificial hip, they attach within minutes. They send signals to recruit others and, once they sense a quorum, they work to build a matrix. Within hours, it encases them like a slimy tortoise shell, which can account for 90% of the mass of the biofilm. Quorum sensing also cues the bacteria to release toxins en masse.

Studying biofilms that form at the interface between agar and plastic using time-lapse photography, Whitchurch has observed these films marching forward like a phalanx. But the microbes also act like organisms far higher up the evolutionary tree. Like sponges, they work together to build complex structures. Within days, small microbial villages may become cities that are millimetres thick, replete with tower blocks and water-filled channels to supply nutrients and remove waste. Individual bacteria can take on specialised roles, be it to produce building blocks for the shield or maintain surface attachment.

“They talk, they build; they’re civil engineers. It’s an amazing time to be a microbiologist,” says Whitchurch. When the biofilm becomes overpopulated or nutrients become scarce, they also release multiple explorer microbes that are carried away by the current.

Whitchurch also stumbled upon another revelation about biofilms in 2002. The slime that encases the film is a complex goo. Costerton referred to it as the glyocalyx, reflecting the understanding that it was primarily made of sugars. Now it’s been dubbed the Extracellular Polymeric Substance, or EPS, to connote that it’s more of a dog’s breakfast – not only a variety of long, sugary molecules, but also bits of proteins, lipids and even snippets of DNA.

This “extracellular” DNA (eDNA) was thought to be refuse, threads of DNA extruded as dying cells burst. But the vast quantity made Whitchurch question that, so she added an enzyme that dissolves DNA to the biofilm. To her amazement, the biofilms shrank. The simple experiment ended up as a ground-breaking publication in the journal Science. It turns out the structural properties of the double helix are exploited by biofilms, especially to reinforce their slime shield. A DNA-dissolving drug (Pulmozyme) has been used in CF patients to help disrupt the biofilm.

The DNA-reinforced slime barrier is only part of the explanation for how biofilms can be up to 10,000 times more resistant to antibiotics than bacteria in the planktonic form. For one thing, most antibiotics throw a spanner in the works of dividing or metabolising cells, but it turns out mature biofilms harbour dormant, spore-like cells in their interior. So any antibiotics that do penetrate the biofilm will not be able to eradicate the so-called “persisters”.

Administering low levels of antibiotics can also backfire. The survivors activate stress-response genes that see them building bigger and more robust biofilms. The members of a biofilm are also immersed in each other’s DNA, allowing for a never-ending swap meet – a challenge when some of the participants carry antibiotic-resistant genes. Microbiologists have long been aware of the so-called horizontal gene transfer. The new understanding of biofilms explains why this is so prevalent.

Biofilms build their own artillery

Biofilms also foil the immune system. And not only by means of their impenetrable slime. In 2007, Høiby's team observed a contingent of immune cells zero in on bacteria – then they saw an ambush. Poking out of the biofilm was a war machine built of sugars and lipids. Called a “rhamnolipid canon”, it blasted holes in the immune cells, a strategy coordinated by quorum sensing.

Unable to clear nasty biofilm infections, immune cells congregate on the outskirts and continue to mount their blunted attack. The toxins, like free radicals, fired at the biofilm end up damaging the surrounding healthy tissue. So, explains Høiby, biofilm infections in cystic fibrosis patients end up destroying lung tissue; in artificial knee joints, they eat away at the bone. And biofilm infections in the stomach, colon, liver and prostate are associated with the development of cancer.

Yet biofilms aren’t all bad. Most of our resident bacteria, our microbiome, resides in biofilms – they are essential to our health. Problems occur when a particular biofilm ecosystem becomes imbalanced.

Meanwhile, the war against bad biofilms needs to be won. Researchers have been like espionage agents, stealing biofilms’ battle plans and cracking their communication codes. And Randy Wolcott’s patients have been benefiting.

The more recent gels include hamamelitannin, an extract of witch-hazel bark that inhibits quorum sensing. Other biofilm-specific treatments that block the communication codes are waiting in the wings. While the biofilm is a mixture of different species, it is no tower of Babel. A chemical called cyclic-di-GMP is a universal signal for bacteria to aggregate. Last year, Høiby’s group showed they could disperse a Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm growing on silicone implants in mice by decreasing the levels of cyclic-di-GMP. Very low concentrations of the gas nitric oxide also act as a dispersal signal for many bacterial species.

The hope is that biofilm-based tactics will disseminate fast. Not only could hundreds of thousands of lives be saved, but we might stop our headlong descent into the “end of antibiotics era”. As Wolcott put it, “the ‘one and done’ strategy of treating infections as if they are planktonic is not and cannot work for biofilm”. But he adds “the good news is we can accumulate new knowledge faster than the bacteria evolve”

This article is based on an article written by Bronwen Morgan that first appeared in Cosmos Magazine in June 2015 www.cosmosmagazine.com, reproduced by kind permission of Cosmos Magazine.

If you would like to find out more or help fund research being undertaken by Cystic Fibrosis WA, please call CEO Nigel Barker on 08 6457 7333, or email ceo@cfwa.org.au. All donations over $2 are tax deductible and can be made online at http://www.cysticfibrosis.org.au/wa/

Your rating